9 FLU VACCINE FACTS

Are Mandates Science-Based?

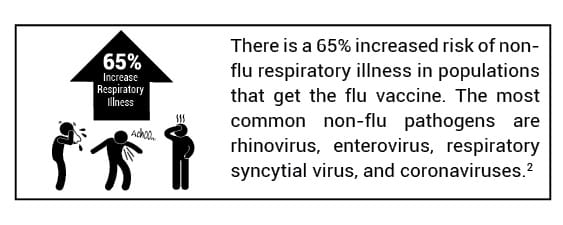

1. TheRE IS A 65% INCREASED RISK OF NON-FLU RESPIRATORY ILLNESS IN POPULATIONS THAT GET THE FLU VACCINE.

1. TheRE IS A 65% INCREASED RISK OF NON-FLU RESPIRATORY ILLNESS IN POPULATIONS THAT GET THE FLU VACCINE.

Although some studies suggest positive effects of the flu vaccine on the incidence of illness caused by flu viruses, that benefit is potentially outweighed by the negative effects of the flu vaccine on the incidence of non-flu respiratory illness.1 To address the concern among patients that the flu vaccine causes illness (i.e., acute respiratory illness), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funded a three-year study,2 published in Vaccine, to analyze the risk of illness after flu vaccination compared to the risk of illness in unvaccinated individuals.

The study, which included healthy subjects, found a 65% increased risk of non-flu acute respiratory illness within 14 days of receiving the flu vaccine. The authors state, “Patients’ experiences of illness after vaccination may be validated by these results.” The most common non-flu pathogens found were rhinovirus, enterovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, and coronaviruses.

This is important because although flu vaccines target a few strains of flu virus, over 200 different viruses cause illnesses that produce the same symptoms — fever, headache, aches, pains, cough, and runny nose — as influenza,3 and more than 85% of acute respiratory illnesses do not involve the flu.4

2. STUDIES SHOW The flu vaccine doesn’t reduce demand on hospitals.

The National Institute of Health (NIH) funded a study5 to measure the effect of seasonal influenza vaccination on hospitalization among the elderly. The study analyzed 170 million episodes of medical care and found that “no evidence indicated that vaccination reduced hospitalizations.”

In addition, a 2018 Cochrane review6 of 52 clinical trials assessing the effectiveness of influenza vaccines did not find a significant difference in hospitalizations between vaccinated and unvaccinated adults. Instead, the reviewers found “low-certainty evidence that hospitalization rates and time off work may be comparable between vaccinated and unvaccinated adults.”

Furthermore, the Mayo Clinic conducted a case-control study7 to analyze the effectiveness of the trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV) in preventing flu hospitalization in children 6 months to 18 years old. The study evaluated the risk of hospitalization in both vaccinated and unvaccinated children over an eight-year period. The authors state: “TIV is not effective in preventing laboratory-confirmed influenza-related hospitalization in children.” Instead, “[W]e found a threefold increased risk of hospitalization in subjects who did get the TIV vaccine.”

3. STUDIES SHOW The flu vaccine doesn’t prevent the spread of the flu.

Households are thought to play a major role in community spread of influenza, and there has been a long history of analyzing family households to study the incidence and transmission of respiratory illnesses of all severities. As such, the CDC funded a study8 of 1,441 participants, both vaccinated and unvaccinated, in 328 households. The study evaluated the flu vaccine’s ability to prevent community-acquired influenza (household index cases) and influenza acquired in people with confirmed household exposure to the flu (secondary cases). Transmission risks were determined and characterized.

In conclusion, the authors state: “There was no evidence that vaccination prevented household transmission once influenza was introduced.”8

Furthermore, a systematic review4 of 50 influenza vaccine studies conducted for the Cochrane Library states: “Influenza vaccines have a modest effect in reducing influenza symptoms and working days lost. There is no evidence that they affect complications, such as pneumonia, or transmission.”

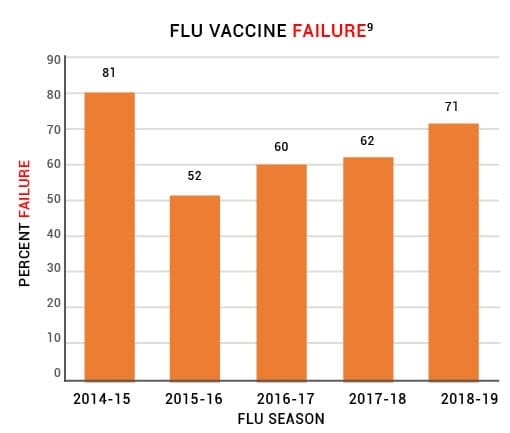

4. The flu vaccine fails to prevent the flu about 65% of the time.

The CDC conducts studies to assess the effects of flu vaccination each flu season to help determine if flu vaccines are working as intended.9 As circulating flu viruses are constantly changing (primarily due to antigenic drift mutations),10 flu vaccines are reformulated regularly based on research that tries to predict which viruses might circulate during the coming flu season.11 Between 2014 and 2019, the CDC estimated the effectiveness of flu vaccines using the Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness (VE) Network,9 a collaboration with participating institutions in five geographic locations.12 The CDC states, “[A]nnual estimates of vaccine effectiveness give a real-world look at how well the vaccine protects against influenza caused by circulating viruses each season.”12

Data from the CDC’s Influenza VE Network indicate a 65% vaccine failure rate between 2014 and 2019 (Fig. 1).9

Figure 1: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data from the U.S. Flu VE

Network indicate that the flu vaccine has failed to prevent the flu about 65% of the time.

5. Repeat doses of the flu vaccine may increase the risk of flu vaccine failure.

Studies have observed that influenza vaccines have low effectiveness in individuals who are vaccinated in two consecutive years.8 A review of 17 influenza vaccine studies published in Expert Review of Vaccines states, “The effects of repeated annual vaccination on individual long-term protection, population immunity, and virus evolution remain largely unknown.”13

6. Death from influenza is rare in children.

Before the widespread use of the influenza vaccine in children, between 2000 and 2003, each year kids age 18 and younger had about 1 in 1.26 million or 0.00008% chance of dying from the flu.14 In a 2004 report, the CDC stated, “Deaths from influenza are uncommon among children with and without high-risk conditions.”15

7. STUDIES SHOW The flu vaccine doesn’t reduce deaths from pneumonia and flu.

The National Vaccine Program Office, a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), funded a study16 to examine flu mortality over the period of 33 years (1968–2001). The study found no decrease in flu mortality associated with the widespread use of the influenza vaccine. The authors state: “We could not correlate increasing vaccination coverage after 1980 with declining mortality rates in any age group… [W]e conclude that observational studies substantially overestimate vaccination benefit.”

Furthermore, the National Institute of Health (NIH) funded a study5 to measure the effect of seasonal influenza vaccination on mortality among the elderly. The study analyzed 7.6 million deaths and found “a sharp increase in influenza vaccination rates at age 65 years with no matching decrease in hospitalization or mortality rates.”

8. STUDIES SHOW Patients don’t benefit from the vaccination of healthcare workers.

A review17 of more than 30 influenza vaccine studies conducted for the Cochrane Library states, “Our review findings have not identified conclusive evidence of benefit of HCW [healthcare workers] vaccination programs on specific outcomes of laboratory-proven influenza, its complications (lower respiratory tract infection, hospitalization or death due to lower respiratory tract illness), or all cause mortality in people over the age of 60.” The authors conclude, “This review does not provide reasonable evidence to support the vaccination of healthcare workers to prevent influenza.” In addition, “There is little evidence to justify medical care and public health practitioners mandating influenza vaccination for healthcare workers.”

9. Flu vaccine mandates are not science-based.

A Cochrane Vaccines Field analysis18 evaluated studies measuring the benefits of flu vaccination. The analysis, published in the BMJ, concludes: “The large gap between policy and what the data tell us (when rigorously assembled and evaluated) is surprising… Evidence from systematic reviews shows that inactivated vaccines have little or no effect on the effects measured… Reasons for the current gap between policy and evidence are unclear, but given the huge resources involved, a re-evaluation should be urgently undertaken.”

References

- Dierig A, Heron LG, Lambert SB, Yin JK, Leask J, Chow MY, Sloots TP, Nissen MD, Ridda I, Booy R. Epidemiology of respiratory viral infections in children enrolled in a study of influenza vaccine effectiveness. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2014 May;8(3):293-301. Epub 2014 Jan 31. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24483149/.

- Rikin S, Jia H, Vargas CY, Castellanos de Belliard Y, Reed C, LaRussa P, Larson EL, Saiman L, Stockwell MS. Assessment of temporally related acute respiratory illness following influenza vaccination. Vaccine. 2018 Apr 5;36(15):1958-64. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7115556/.

- Demicheli V, Jefferson T, Al-Ansary LA, Ferroni E, Rivetti A, Di Pietrantonj C. Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy adults. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2014 Mar 13;(3):CD001269. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001269.pub5/epdf/full.

- Jefferson T, Di Pietrantonj C, Rivetti A, Bawazeer GA, Al-Ansary LA, Ferroni E. Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy adults. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2010 Jul 7;(7):CD001269. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001269.pub4/full.

- Anderson ML, Dobkin C, Gorry D. The effect of influenza vaccination for the elderly on hospitalization and mortality: an observational study with a regression discontinuity design. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Apr 7;172(7):445-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32120383/.

- Demicheli V, Jefferson T, Ferroni E, Rivetti A, Di Pietrantonj C. Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Feb 1;2(2):CD001269. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001269.pub6/full.

- Joshi AY, Iyer VN, Hartz MF, Patel AM, Li JT. Effectiveness of trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in influenza-related hospitalization in children: a case-control study. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2012 Mar-Apr;33(2):e23-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22525386/.

- Ohmit SE, Petrie JG, Malosh RE, Cowling BJ, Thompson MG, Shay DK, Monto AS. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the community and the household. Clin Infect Dis. 2013 May;56(10):1363. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3693492/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. CDC seasonal flu vaccine effectiveness studies; [cited 2024 Aug 31]. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/cdc-seasonal-flu-vaccine-effectiveness-studies.

- Shao W, Li X, Goraya MU, Wang S, Chen JL. Evolution of influenza A virus by mutation and re-assortment. Int J Mol Sci. 2017 Aug 7;18(8):1650. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5578040/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Selecting viruses for the seasonal influenza vaccine; [cited 2024 Aug 31]. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/cdc-selecting-viruses-for-the-seasonal-influenza-vaccine.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. How flu vaccine effectiveness and efficacy are measured; [cited 2020 May 14]. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/cdc-how-flu-vaccine-effectiveness-and-efficacy-are-measured.

- Belongia EA, Skowronski DM, McLean HQ, Chambers C, Sundaram ME, De Serres G. Repeated annual influenza vaccination and vaccine effectiveness: review of evidence. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2017 Jul;16(7):723,733. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28562111/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. CDC wonder: about underlying cause of death, 1999-2018; [cited 2020 May 2]. https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html; query for death from influenza, 2000-2003. Between 2000 and 2003, there were 61 annual deaths from influenza out of 77 million children age 18 and younger, about 1 death in 1.26 million.

- Harper SA, Fukuda K, Uyeki TM, Cox NJ, Bridges CB; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Prevention and control of influenza: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2004 May 28;53(RR-6):1-40. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5306a1.htm.

- Simonsen L, Reichert TA, Viboud C, Blackwelder WC, Taylor RJ, Miller MA. Impact of influenza vaccination on seasonal mortality in the US elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Feb 14;165(3):265-72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15710788/.

- Thomas RE, Jefferson T, Lasserson TJ. Influenza vaccination for healthcare workers who care for people aged 60 or older living in long-term care institutions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Jun 2;(6):CD005187. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD005187.pub5/full.

- Jefferson T. Influenza vaccination: policy versus evidence. BMJ. 2006 Oct 28;333(7574):912-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1626345/.

Published 2020 Oct; updated 2024 Oct