Hepatitis B: What You Need to Know

1. WHAT IS HEPATITIS B?

1. WHAT IS HEPATITIS B?

Hepatitis B is a viral infection.

- Infants and children usually don’t experience any symptoms of hepatitis B, and about 50% of adults don’t experience any symptoms.1

- In noticeable cases, hepatitis B symptoms can include a prodromal (initial) phase of 3–10 days of loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, fever, headache, stomachache, muscle pain, or joint pain. This phase can be followed by 1–3 weeks of jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes) and tenderness of the liver.2

- About 85% of new hepatitis B infections are benign and not reported to public health departments.3

- Most fatal cases of hepatitis B occur later in life, usually after age 55, in situations when chronic infection leads to liver cirrhosis or liver cancer.2,4,5

2. HOW IS HEPATITIS B TRANSMITTED?

Hepatitis B is spread through the mixing of bodily fluids with those of an infected individual, usually involving infected blood. In the United States, the most common routes of transmission are by sexual contact among heterosexuals with multiple partners or men who have sex with men, and injection drug use.2 The virus can also be transmitted by being born to an infected mother.2 Casual contact with an infected individual’s saliva, tears, sweat, and urine are unlikely modes of transmission.2 Hepatitis B is not transmitted by breastfeeding, kissing, hugging, holding hands, coughing, sneezing, or sharing dishes, eating utensils, or drinking glasses.6

Hepatitis B is spread through the mixing of bodily fluids with infected blood. Hepatitis B is not spread by breastfeeding, kissing, hugging, holding hands, coughing, sneezing, or sharing dishes, eating utensils, or drinking glasses.6

Hepatitis B is spread through the mixing of bodily fluids with infected blood. Hepatitis B is not spread by breastfeeding, kissing, hugging, holding hands, coughing, sneezing, or sharing dishes, eating utensils, or drinking glasses.6

3. WHAT ARE THE RISKS?

3. WHAT ARE THE RISKS?

Prior to 1991, before widespread use of the hepatitis B vaccine began, hepatitis B was a disease of low incidence.

- New hepatitis B infections occurred in about 1 in 1,700 in the U.S. population.7

- Hepatitis B occurred even less frequently among children, comprising only 8% of all new hepatitis B infections: about 1 in 3,600 children.8

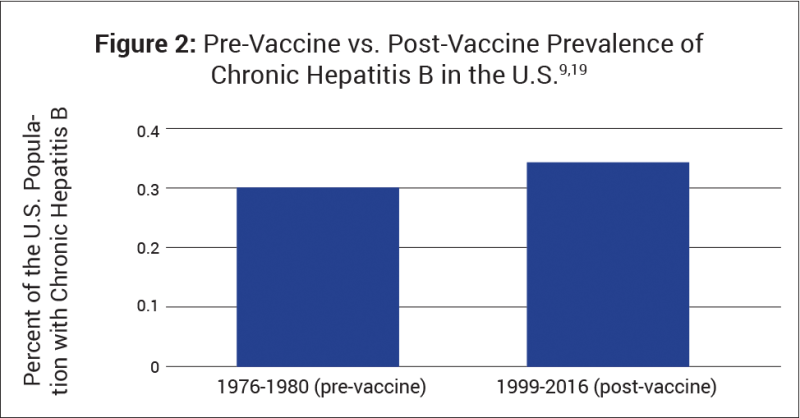

Despite widespread use of the hepatitis B vaccine for more than 25 years, the prevalence of chronic hepatitis B infection in the U.S. has remained about the same since 1976, when the rate was 0.3% of the population.9 It is estimated that between 1 in 60,000 (0.0017%) and 1 in 80,000 (0.0013%) individuals die annually from hepatitis B-related liver cirrhosis or liver cancer.10

The great majority of hepatitis B infections occur in people who:

- Engage in high-risk sexual behavior or intravenous drug use.

- 79% of hepatitis B infections in adults and adolescents occur among heterosexuals with multiple partners, men who have sex with men, or injection drug users.2

- Live with an infected individual.

- Before widespread use of the hepatitis B vaccine, 50% of hepatitis B infections in children occurred in babies born to infected mothers.2

- 67% of children infected with hepatitis B after birth live with an infected individual.11

- Live in communities where hepatitis B infection is unusually prevalent.

- Most infected adults and adolescents with no known source of exposure live in communities where hepatitis B prevalence is three to five times greater than in the general population.12

- The prevalence of hepatitis B in communities that emigrated to the U.S. from countries with high hepatitis B endemicity is 14 to 28 times greater than in the general population.13

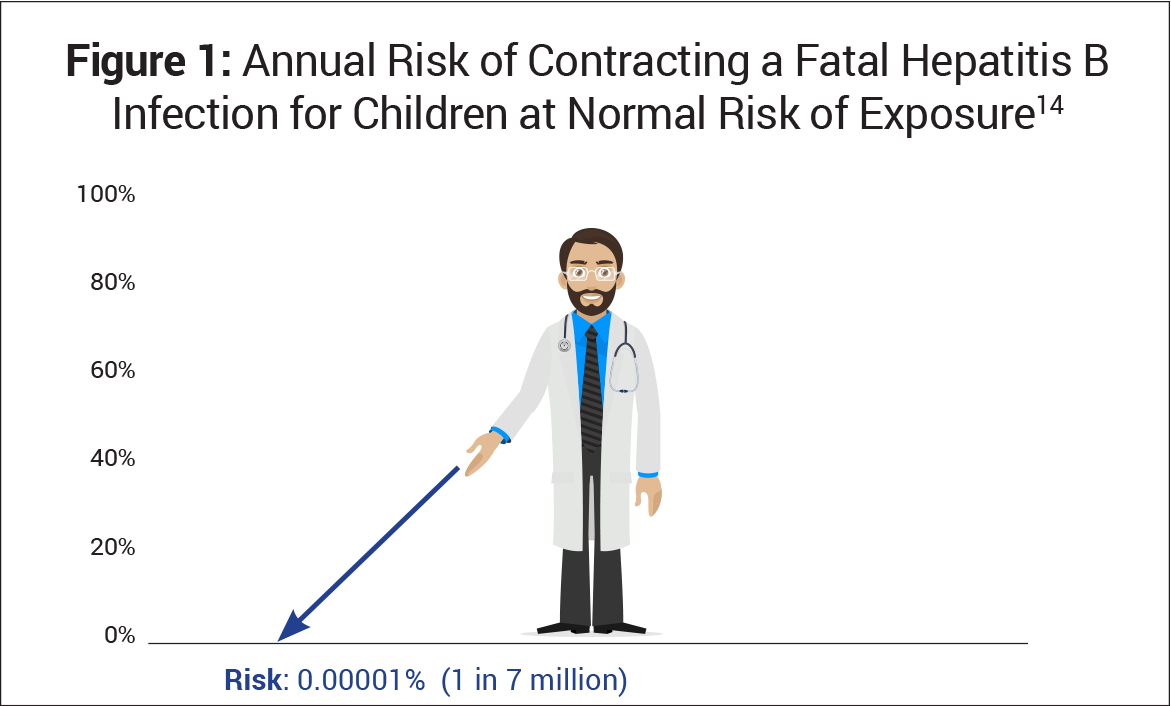

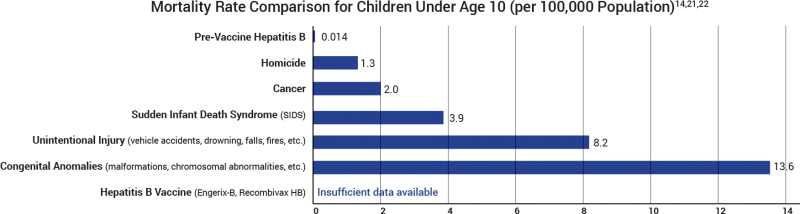

Before widespread use of the hepatitis B vaccine, annually less than 1 in 7,000,000 or 0.00001% of children at normal risk of exposure (i.e., were not born to an infected mother, did not live with an infected individual, and did not live in a community with a large number of infected individuals) contracted chronic hepatitis B that led to fatal liver cirrhosis or cancer later in life (Fig. 1).14

4. WHAT TREATMENTS ARE AVAILABLE?

Because hepatitis B resolves on its own in most cases, usually only supportive treatment is necessary. As such, treatment options include the following:

- Rest and hydration

- Antiviral medicines, available to treat chronically infected individuals with high levels of both the hepatitis B virus and liver enzymes in the blood for at least six months — options include interferons or adefovir, entecavir, lamivudine, telbivudine, and tenofovir15

- Immune globulin, available for individuals who are exposed to infection, including infants of chronically infected mothers and immunocompromised patients, such as those on chemotherapy2

5. ARE PREGNANT WOMEN TESTED FOR HEPATITIS B?

5. ARE PREGNANT WOMEN TESTED FOR HEPATITIS B?

Yes. Pregnant women are given a blood test for hepatitis B when seeing the doctor. If a woman has not seen a doctor during pregnancy, she will receive a test at the hospital when she gives birth.16 About 99.7% of women in the U.S. are hepatitis B negative.17

6. WHAT ABOUT THE HEPATITIS B VACCINE?

6. WHAT ABOUT THE HEPATITIS B VACCINE?

The hepatitis B vaccine was first licensed in the U.S. in 1981 for use in high-risk populations, and then in 1991 the recommendation began for universal infant vaccination. It has significantly reduced the incidence of reported (i.e., noticeable) cases of acute hepatitis B infections in children and adolescents;2 however, about 50% of vaccinated children lose their immunity by age 5,18 and the vaccine has not made a measurable impact on the prevalence of chronic hepatitis B infection (Fig. 2).9,19

The manufacturer’s package insert contains information about vaccine ingredients, adverse reactions, and vaccine evaluations. For example, “Recombivax HB has not been evaluated for its carcinogenic or mutagenic potential, or its potential to impair fertility.”20 Furthermore, the risk of permanent injury or death from the hepatitis B vaccine has not been proven to be less than that of hepatitis B for children at normal risk of exposure (Fig. 3).21

Figure 3: Most fatal cases of hepatitis B occur later in life, after age 55. This graph shows the death rate of children under age 10 at normal risk of exposure (i.e., were not born to an infected mother, did not live with an infected individual, and did not live in a community with a large number of infected individuals) who contracted hepatitis B and would die of cirrhosis or cancer later in life. The rate was 0.014 per 100,000 before the widespread use of the vaccine and is compared to the leading causes of death in children under age 10 in 2015, when the death rate per 100,000 for homicide was 1.3, followed by cancer (2.0), SIDS (3.9), unintentional injury (8.2), and congenital anomalies (13.6). The rate of death or permanent injury from the hepatitis B vaccine (Engerix-B, Recombivax HB) is unknown because the research studies available are not able to measure it with sufficient accuracy.

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. 14th ed. Hall E, Wodi AP, Hamborsky J, Morelli V, Schillie S, editors. Washington, D.C.: Public Health Foundation; 2021. 144. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/cdc-pink-book-14th-edition-2021/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. 13th ed. Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe S, editors. Washington, D.C.: Public Health Foundation; 2015. 151-7, 169. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/cdc-pink-book-13th-edition-2015/.

- Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, Harris A, Haber P, Ward JW, Nelson NP. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018 Jan 12;67(1):3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5837403/; only 1 in 6.5 (15.4%) cases of hepatitis B are reported to government agencies, such as the CDC.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States. MMWR. 2006 Dec 8;55(RR-16):3. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5516.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. CDC wonder: underlying cause of death, 1999-2020; [cited 2022 May 9]. https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html. Query for deaths from cirrhosis and liver cancer, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Hepatitis B: are you at risk? 2013 Jun. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis-b/media/FactSheet-HepBAreYouAtRisk.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. 13th ed. Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe S, editors. Washington, D.C.: Public Health Foundation; 2015. Appendix E5. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/cdc-pink-book-13th-edition-appendix-e-2015/; between 1988 and 1990, annually there were about 22,500 reported cases of hepatitis B out of a population of 250 million. These reported cases comprised 15.4% of 146,000 cases,3 therefore hepatitis B was contracted by 1 in 1,700 (146,000/250 million).

- In 1989, 8% of 146,000 new hepatitis B infections occurred in children — about 11,700 cases out of 42 million children (1 in 3,600).2,7

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC guidance for evaluating health-care personnel for hepatitis B virus protection and for administering postexposure management. MMWR. 2013 Dec 20; 62(10):4-5. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6210a1.htm.

- An estimated 3,000 to 4,000 people die of hepatitis B-related cirrhosis each year in the U.S. An estimated 1,000 to 1,500 people die of hepatitis B-related liver cancer each year in the U.S. This results in 4,000 to 5,500 hepatitis B-related deaths out of a population of 320 million (1 in 60,000 to 1 in 80,000).2

- Armstrong GL, Mast EE, Wojczynski M, Margolis HS. Childhood hepatitis B virus infections in the United States before hepatitis B immunization. Pediatrics. 2001 Nov; 108(5):1126. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11694691/.

- Alter MJ, Hadler SC, Margolis HS, Alexander WJ, Hu PY, Judson FN, Mares A, Miller JK, Moyer LA. The changing epidemiology of hepatitis B in the United States. Need for alternative vaccination strategies. JAMA. 1990 Mar 2; 263(9):1222. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2304237/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. 10th ed. Atkinson W, Hamborsky J, McIntyre L, Wolfe C, editors. Washington, D.C.: Public Health Foundation; 2007. 218. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/cdc-pink-book-10th-edition-hepatitis-b-2007.

- Magno H, Golomb B. Measuring the benefits of mass vaccination programs in the United States. Vaccines. 2020 Sep 29;8(4):561. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33003480/.

- Cigna. Bloomfield (CT): Cigna. Hepatitis B: should I take antiviral medicine for chronic hepatitis B? [cited 2022 May 7]. https://www.cigna.com/knowledge-center/hw/medical-topics/hepatitis-b-uf1166.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Hepatitis B and a healthy baby; 2015 May 31 [cited 2022 May 22]: 4. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/cdc-hepatitis-b-and-a-healthy-baby.

- In 2012 in the U.S., about 850,000 people (0.3%) out of a population of 314 million were chronically infected with hepatitis B. Consequently, about 99.7% (313/314) of the population was hepatitis B negative.3

- Puliyel J, Naik P, Puliyel A, Agarwal K, Lal V, Kansal N, Nandan D, Tripathi V, Tyagi P, Singh SK, Srivastava R, Sharma U, Sreenivas V. Evaluation of the protection provided by hepatitis B vaccination in India. Indian J Pediatr. 2018 Jul;85(7):514. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29318526/.

- Lim JK, Nguyen MH, Kim WR, Gish R, Perumalswami P, Jacobson IM. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020 Sep;115(9):1432. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32483003/.

- Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Whitehouse Station (NJ): Merck and Co., Inc. Recombivax HB Hepatitis B Vaccine (Recombinant); revised 2018 Dec [cited 2022 May 2]. https://www.fda.gov/media/74274/download.

- Physicians for Informed Consent. Newport Beach (CA): Physicians for Informed Consent. Hepatitis B – vaccine risk statement (VRS). Hepatitis B vaccine: is it safer than hepatitis B? 2022 Aug. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/hepatitis-b-vrs.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 10 leading causes of death by age group, United States—2015. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/cdc-leading-causes-of-death-age-group-2015/.

Published 2022 Aug; updated 2024 Oct