Measles

What You Need to Know

What Is Measles?

Measles is a self-limiting childhood viral infection.

- Measles symptoms include a prodromal (initial) phase of cough, runny nose, eye irritation and fever, followed by a generalized rash on days 4–10 of the illness.1

- Measles is contagious during the prodromal phase and for 3-4 days after rash onset.1

- Most measles cases are benign and not reported to public health departments.2

- Before the measles mass vaccination program was introduced, nearly everyone contracted measles and obtained lifetime immunity by age 15.1

- Rarely, measles can cause brain damage and death.3,4

What Are the Risks?

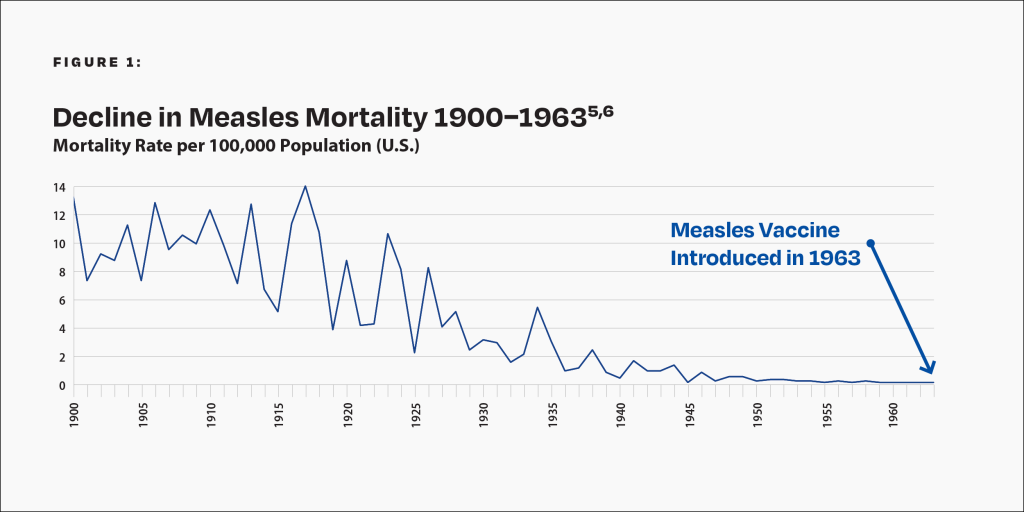

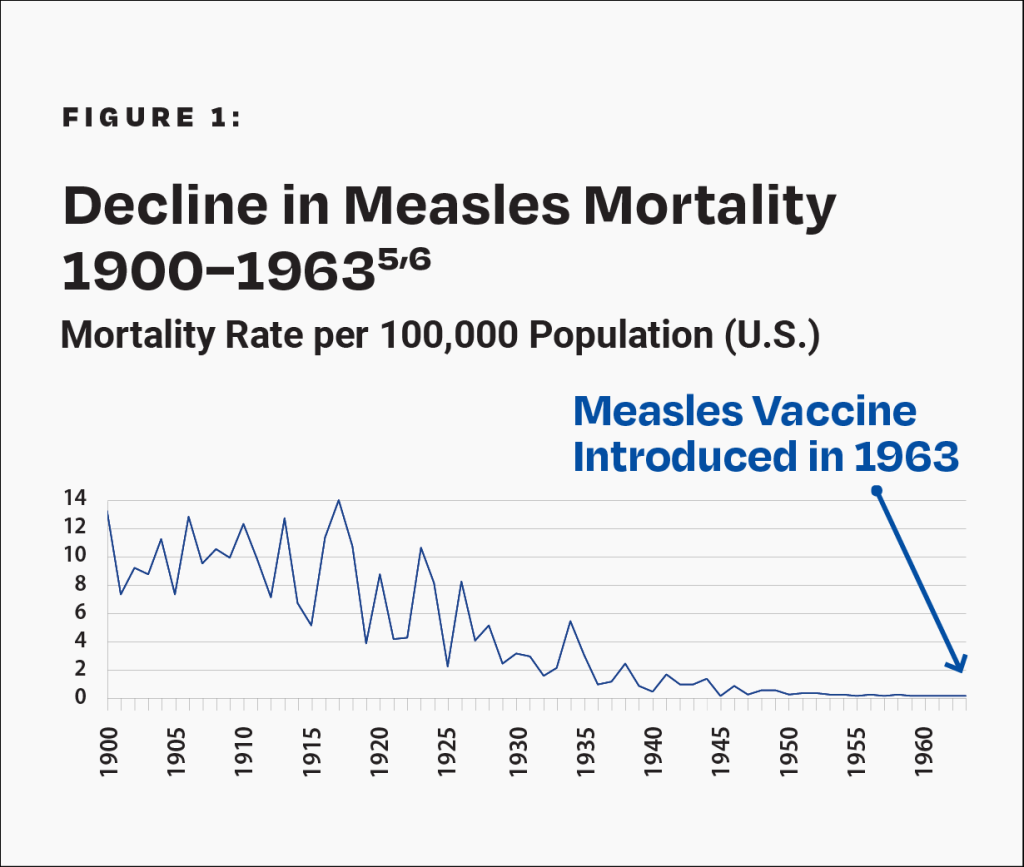

In the modern era, it is rare to suffer permanent disability or death from measles in the United States. Between 1900 and 1963, the mortality rate of measles dropped from 13.3 per 100,000 to 0.2 per 100,000 in the population, due to advancements in living conditions, nutrition, and health care — a 98% decline (Fig. 1).5,6 Malnutrition, especially vitamin A deficiency, is a primary cause of more than 100,000 measles deaths annually in underdeveloped nations.7,8 In the U.S. and other developed countries, 92% of hospitalized measles cases are low in vitamin A.9

Research studies and national tracking of measles have documented the following:

- 1 in 10,000 or 0.01% of measles cases are fatal.3

- 3 to 3.5 in 10,000 or 0.03–0.035% of measles cases result in seizure.10

- 1 in 20,000 or 0.005% of measles cases result in measles encephalitis.4

- 1 in 80,000 or 0.00125% of cases result in permanent disability from measles encephalitis.4

- 7 in 1,000 or 0.7% of cases are hospitalized.11

- 6 to 22 in 1,000,000 or 0.0006–0.0022% of cases result in subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE).12

- 1 in 93,000 or 0.001% of measles cases with normal levels of vitamin A result in permanent disability or death.13

Measles death declined 98% from 1900 to 1963, before the measles vaccine was introduced.

What Is Measles?

Measles is a self-limiting childhood viral infection.

- Measles symptoms include a prodromal (initial) phase of cough, runny nose, eye irritation and fever, followed by a generalized rash on days 4–10 of the illness.1

- Measles is contagious during the prodromal phase and for 3-4 days after rash onset.1

- Most measles cases are benign and not reported to public health departments.2

- Before the measles mass vaccination program was introduced, nearly everyone contracted measles and obtained lifetime immunity by age 15.1

- Rarely, measles can cause brain damage and death.3,4

What Are the Risks?

In the modern era, it is rare to suffer permanent disability or death from measles in the United States. Between 1900 and 1963, the mortality rate of measles dropped from 13.3 per 100,000 to 0.2 per 100,000 in the population, due to advancements in living conditions, nutrition, and health care — a 98% decline (Fig. 1).5,6 Malnutrition, especially vitamin A deficiency, is a primary cause of more than 100,000 measles deaths annually in underdeveloped nations.7,8 In the U.S. and other developed countries, 92% of hospitalized measles cases are low in vitamin A.9

Research studies and national tracking of measles have documented the following:

- 1 in 10,000 or 0.01% of measles cases are fatal.3

- 3 to 3.5 in 10,000 or 0.03–0.035% of measles cases result in seizure.10

- 1 in 20,000 or 0.005% of measles cases result in measles encephalitis.4

- 1 in 80,000 or 0.00125% of cases result in permanent disability from measles encephalitis.4

- 7 in 1,000 or 0.7% of cases are hospitalized.11

- 6 to 22 in 1,000,000 or 0.0006–0.0022% of cases result in subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE).12

- 1 in 93,000 or 0.001% of measles cases with normal levels of vitamin A result in permanent disability or death.13

Measles death declined 98% from 1900 to 1963, before the measles vaccine was introduced.

What Treatments Are Available for Measles?

Since measles resolves on its own in almost all cases, usually only rest and hydration are necessary. When treatment is recommended, options include the following:

- High-dose vitamin A14

- Immune globulin (available for immunocompromised patients, such as those on chemotherapy)15

- The antiviral medication, ribavirin16

Are There Any Benefits from Getting Measles?

There are studies that suggest a link between naturally acquired measles infection and a reduced risk of Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, as well as a reduced risk of atopic diseases such as hay fever, eczema and asthma.17-21 In addition, measles infections are associated with a lower risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease in adulthood.22 Moreover, infants born to mothers who have had naturally acquired measles are protected from measles via maternal immunity longer than infants born to vaccinated mothers.23

What About the Vaccine for Measles?

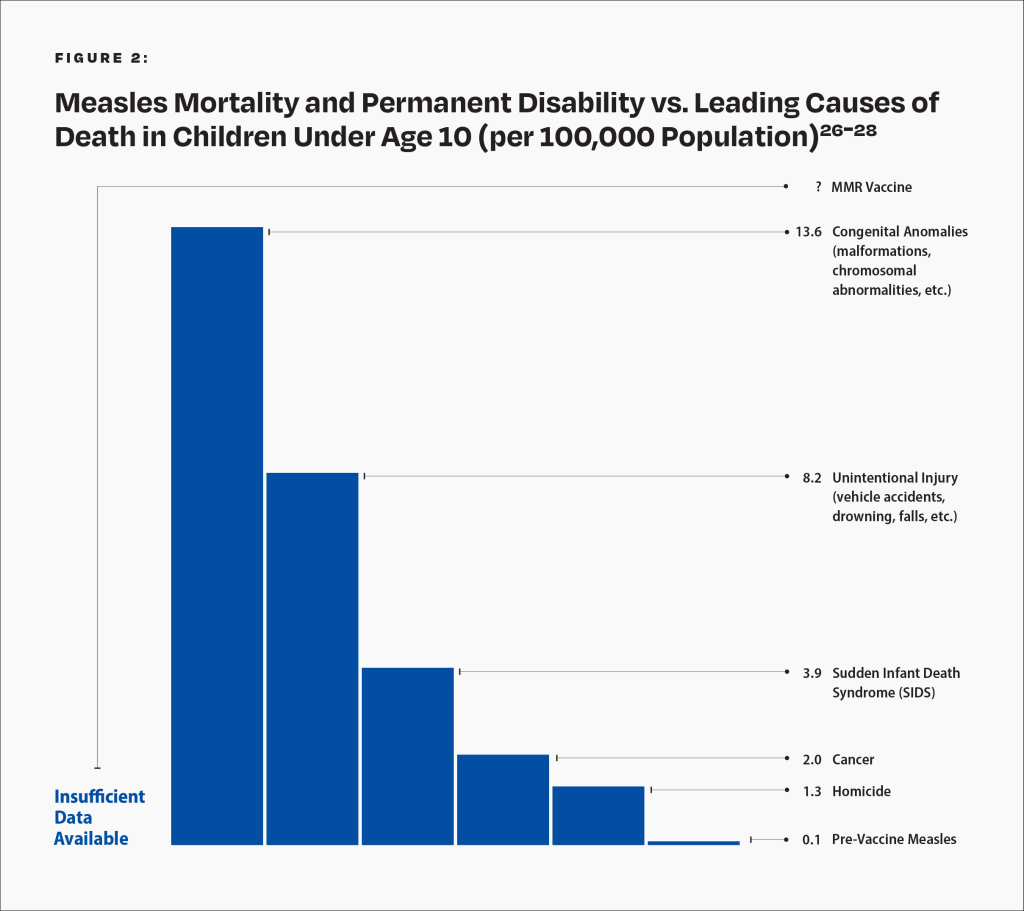

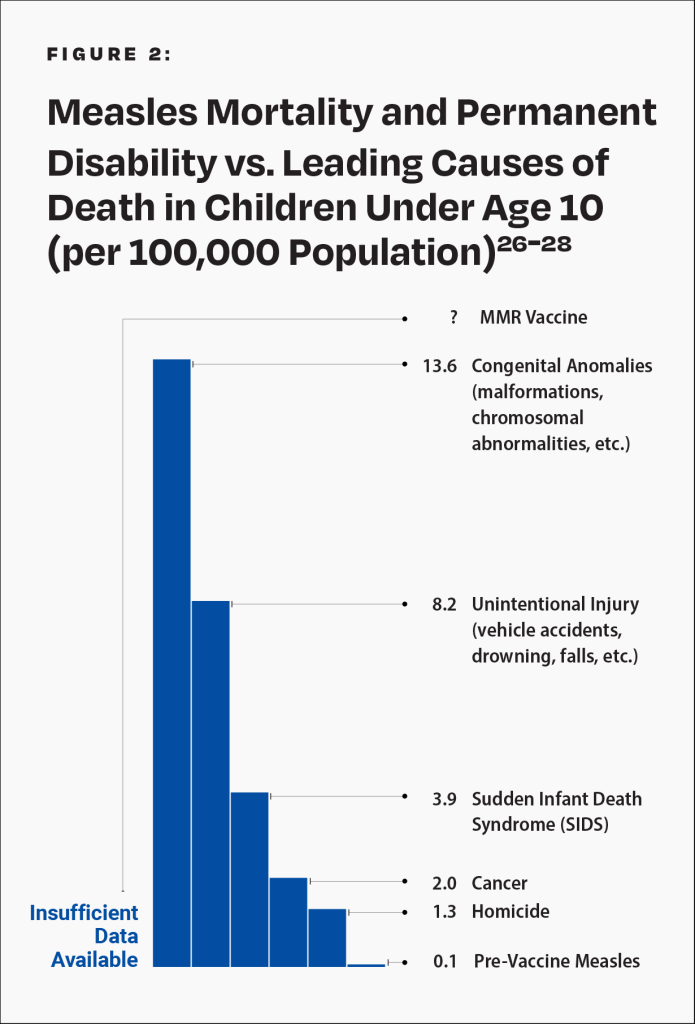

The measles vaccine was introduced in the U.S. in 1963 and is now available as a component of the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. It has significantly reduced the number of reported measles cases; however, immunity from the vaccine wanes so that by age 15, about 60% of vaccinated children are susceptible to subclinical infection with measles virus, and by age 24–26, a projected 33% of vaccinated adults are susceptible to clinical infection.24 The manufacturer’s package insert contains information about vaccine ingredients, adverse reactions, and vaccine evaluations. For example, “M-M-R II vaccine has not been evaluated for carcinogenic or mutagenic potential or impairment of fertility.”25 Furthermore, the risk of permanent injury and death from the MMR vaccine has not been proven to be less than that of measles (Fig. 2).26

This graph shows the measles mortality and permanent disability rate of children under age 10 with normal levels of vitamin A before the vaccine was introduced and compares it to the leading causes of death in children under age 10 today. Hence, in the pre-vaccine era, the measles mortality and permanent disability rate per 100,000 was 0.1 for children under age 10 with normal levels of vitamin A. In 2015, the mortality rate per 100,000 for homicide was 1.3, followed by cancer (2.0), SIDS (3.9), unintentional injury (8.2), and congenital anomalies (13.6). The rate of death or permanent disability from the MMR vaccine is unknown because the research studies available are not able to measure it with sufficient accuracy.

What Treatments Are Available for Measles?

Since measles resolves on its own in almost all cases, usually only rest and hydration are necessary. When treatment is recommended, options include the following:

- High-dose vitamin A14

- Immune globulin (available for immunocompromised patients, such as those on chemotherapy)15

- The antiviral medication, ribavirin16

Are There Any Benefits from Getting Measles?

There are studies that suggest a link between naturally acquired measles infection and a reduced risk of Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, as well as a reduced risk of atopic diseases such as hay fever, eczema and asthma.17-21 In addition, measles infections are associated with a lower risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease in adulthood.22 Moreover, infants born to mothers who have had naturally acquired measles are protected from measles via maternal immunity longer than infants born to vaccinated mothers.23

What About the Vaccine for Measles?

The measles vaccine was introduced in the U.S. in 1963 and is now available as a component of the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. It has significantly reduced the number of reported measles cases; however, immunity from the vaccine wanes so that by age 15, about 60% of vaccinated children are susceptible to subclinical infection with measles virus, and by age 24–26, a projected 33% of vaccinated adults are susceptible to clinical infection.24 The manufacturer’s package insert contains information about vaccine ingredients, adverse reactions, and vaccine evaluations. For example, “M-M-R II vaccine has not been evaluated for carcinogenic or mutagenic potential or impairment of fertility.”25 Furthermore, the risk of permanent injury and death from the MMR vaccine has not been proven to be less than that of measles (Fig. 2).26

This graph shows the measles mortality and permanent disability rate of children under age 10 with normal levels of vitamin A before the vaccine was introduced and compares it to the leading causes of death in children under age 10 today. Hence, in the pre-vaccine era, the measles mortality and permanent disability rate per 100,000 was 0.1 for children under age 10 with normal levels of vitamin A. In 2015, the mortality rate per 100,000 for homicide was 1.3, followed by cancer (2.0), SIDS (3.9), unintentional injury (8.2), and congenital anomalies (13.6). The rate of death or permanent disability from the MMR vaccine is unknown because the research studies available are not able to measure it with sufficient accuracy.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. 13th ed. Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe S, editors. Washington, D.C.: Public Health Foundation; 2015. 209-15. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/cdc-pink-book-13th-edition-2015/.

- Centers for Disease Control. Measles prevention: recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP). MMWR. 1989 Dec;38(S-9):1. https://www.cdc.gov/Mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00041753.htm; between 1959 and 1962, annually there were about 4 million cases, of which 440,0005 (11%) were reported.

- Langmuir AD, Henderson DA, Serfling RE, Sherman IL. The importance of measles as a health problem. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1962 Feb;52(2)Suppl:1-4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1522578/; between 1959 and 1962, annually there were 400 measles deaths5 out of 4 million cases2, about 1 in 10,000 cases.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. 13th ed. Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe S, editors. Washington, D.C.: Public Health Foundation; 2015. 210. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/cdc-pink-book-13th-edition-2015/; measles surveillance in the 1980s and 1990s showed that there are half as many cases of measles encephalitis as there are measles deaths, 1 in 20,000 cases (50% of 1 in 10,000 cases of death). Of these cases, 25% (1 in 80,000 cases) result in residual neurological injury.3

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. 13th ed. Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe S, editors. Washington, D.C.: Public Health Foundation; 2015. Appendix E3. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/cdc-pink-book-13th-edition-and-appendix-e-2015-combo.

- Grove RD; Hetzel AM; U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Vital statistic rates in the United States 1940-1960. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office;1968. 559-603. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsus/vsrates1940_60.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control. Current trends measles — United States, 1990, June 1991. MMWR. 1991 Jun;40(22):369-72. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00001999.htm; in 1990, there were 13,310 reported cases of measles under age 5 (48.1% of 27,672) of which 49 were fatal, resulting in case fatality rate of 0.37%.

- World Health Organization. Measles vaccines: WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2009 Aug 28;84(35):350. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/241404/WER8435.PDF?sequence=1; the measles case-fatality rate for young children in underdeveloped nations, where vitamin A deficiency is prevalent, is about 5–10% of reported cases, 14 to 27 times higher than in developed countries.7

- Magno H, Golomb B. Measuring the benefits of mass vaccination programs in the United States. Vaccines. 2020 Sep 29;8(4):3-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33003480/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. 13th ed. Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe S, editors. Washington, D.C.: Public Health Foundation; 2015. 210. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/cdc-pink-book-13th-edition-2015/; measles surveillance in the 1980s and 1990s showed that there are 3 to 3.5 times more measles seizures than measles deaths (3 to 3.5 per 10,000 cases).3

- Centers for Disease Control. Current trends measles — United States, 1990, June 1991. MMWR. 1991 Jun;40(22):369-72. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00001999.htm; measles surveillance in 1990 showed that there are about 70 times more measles hospitalizations than measles deaths (7 per 1,000 cases).3

- Merck. Whitehouse Station (NJ): Merck and Co., Inc. M-M-R II (measles, mumps, and rubella virus vaccine live); revised 2015 Oct. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/merck-mmr-measles-mumps-rubella-ii-package-insert.

- Butler JC, Havens PL, Sowell AL, Huff DL, Peterson DE, Day SE, Chusid MJ, Bennin RA, Circo R, Davis JP. Measles severity and serum retinol (vitamin A) concentration among children in the United States. Pediatrics. 1993 Jun;91(6):1177-81. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8502524/; about 5% of children have low levels of vitamin A, therefore of the 4 million annual measles cases before the vaccine,2 3.8 million (95%) have normal levels of vitamin A. Before the vaccine, 41 annual measles cases with normal levels of vitamin A resulted in permanent disability or death,9 therefore, the risk of permanent disability or death for measles cases with normal levels of vitamin A is 41 in 3.8 million (1 in 93,000).

- Perry RT, Halsey NA. The clinical significance of measles: a review. J Infect Dis. 2004 May 1;189 Suppl 1:S4-16. https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/189/Supplement_1/S4/823958.

- California Department of Public Health. Sacramento (CA): California Health and Human Services Agency. Measles investigation quicksheet: August 2023; [cited 2023 Dec 26]. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/CDPH%20Document%20Library/Immunization/Measles-Quicksheet.pdf.

- Roy Moulik N, Kumar A, Jain A, Jain P. Measles outbreak in a pediatric oncology unit and the role of ribavirin in prevention of complications and containment of the outbreak. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013 Oct;60(10):E122-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23629813/.

- Alexander FE, Jarrett RF, Lawrence D, Armstrong AA, Freeland J, Gokhale DA, Kane E, Taylor GM, Wright DH, Cartwright RA. Risk factors for Hodgkin’s disease by Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) status: prior infection by EBV and other agents. Br J Cancer. 2000 Mar;82(5):1117-21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2374437/.

- Glaser SL, Keegan TH, Clarke CA, Trinh M, Dorfman RF, Mann RB, DiGiuseppe JA, Ambinder RF. Exposure to childhood infections and risk of Epstein-Barr virus—defined Hodgkin’s lymphoma in women. Int J Cancer. 2005 Jul 1;115(4):599-605. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ijc.20787.

- Montella M, Maso LD, Crispo A, Talamini R, Bidoli E, Grimaldi M, Giudice A, Pinto A, Franceschi S. Do childhood diseases affect NHL and HL risk? A case-control study from northern and southern Italy. Leuk Res. 2006 Aug;30(8):917-22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16406019/.

- Shaheen SO, Barker DJP, Heyes CB, Shiell AW, Aaby P, Hall AJ, Goudiaby A. Measles and atopy in Guinea-Bissau. Lancet. 1996 Jun 29;347(9018):1792-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8667923/.

- Rosenlund H, Bergström A, Alm JS, Swartz J, Scheynius A, van Hage M, Johansen K, Brunekreef B, von Mutius E, Ege MJ, Riedler J, Braun-Fahrländer C, Waser M, Pershagen G; PARSIFAL Study Group. Allergic disease and atopic sensitization in children in relation to measles vaccination and measles infection. Pediatrics. 2009 Mar;123(3):771-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19255001/.

- Kubota Y, Iso H, Tamakoshi A, JACC Study Group. Association of measles and mumps with cardiovascular disease. The Japan Collaborative Cohort (JACC) study. Atherosclerosis. 2015 Aug;241(2):682-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26122188/.

- Waaijenborg S, Hahné SJ, Mollema L, Smits GP, Berbers GA, van der Klis FR, de Melker HE, Wallinga J. Waning of maternal antibodies against measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella in communities with contrasting vaccination coverage. J Infect Dis. 2013 Jul;208(1):10-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4043230/.

- LeBaron CW, Beeler J, Sullivan BJ, Forghani B, Bi D, Beck C, Audet S, Gargiullo P. Persistence of measles antibodies after 2 doses of measles vaccine in a postelimination environment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007 Mar;161(3):294-301. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17339511/; children with measles antibody levels less than 900 mIU/mL are susceptible to subclinical infection with measles virus but not to clinical infection. About 60% of children 15 years of age have a measles antibody level less than 900 mIU/mL.

- Merck. Rahway (NJ): Merck and Co., Inc. M-M-R II (measles, mumps, and rubella virus vaccine live); revised 2023 Oct [cited 2024 Jan 27]. 8. https://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/m/mmr_ii/mmr_ii_pi.pdf.

- Physicians for Informed Consent. Newport Beach (CA): Physicians for Informed Consent. MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) – vaccine risk statement (VRS); 2024 Aug. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/mmr-vrs.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 10 leading causes of death by age group, United States—2015. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/cdc-leading-causes-of-death-age-group-2015/.

- Before the vaccine, 41 annual measles cases with normal levels of vitamin A resulted in permanent disability or death of which 91% (37) were under age 10.9 About 5% of children have low levels of vitamin A,13 therefore there are about 38 million (95% of 40 million) children under age 10 with normal levels of vitamin A. Consequently, the annual rate of measles permanent disability or death for that population is 37 out of 38 million (1 in a million).

Published 2017 Oct; updated 2024 Dec

Measles – Disease Information Statement (DIS)