Polio: What You Need to Know

1. WHAT IS POLIO?

1. WHAT IS POLIO?

Polio is an infection caused by the poliovirus.

- About 95% of polio infections have no symptoms (asymptomatic).1

- In noticeable cases, polio can cause low-grade fever, sore throat, and other flu-like symptoms.2,3 After several days of initial symptoms, some people develop stiffness of the neck, back, or legs.2

- About 1 in 200 to 1 in 2,000 (0.5%–0.05%) polio infections result in paralysis (paralytic poliomyelitis),3 and more than 84% of those cases recover without disability.4

2. HOW IS POLIO TRANSMITTED?

Polio is generally spread through fecal-oral contact, but spread through oral-oral contact is also possible.5

3. WHAT ARE THE RISKS?

3. WHAT ARE THE RISKS?

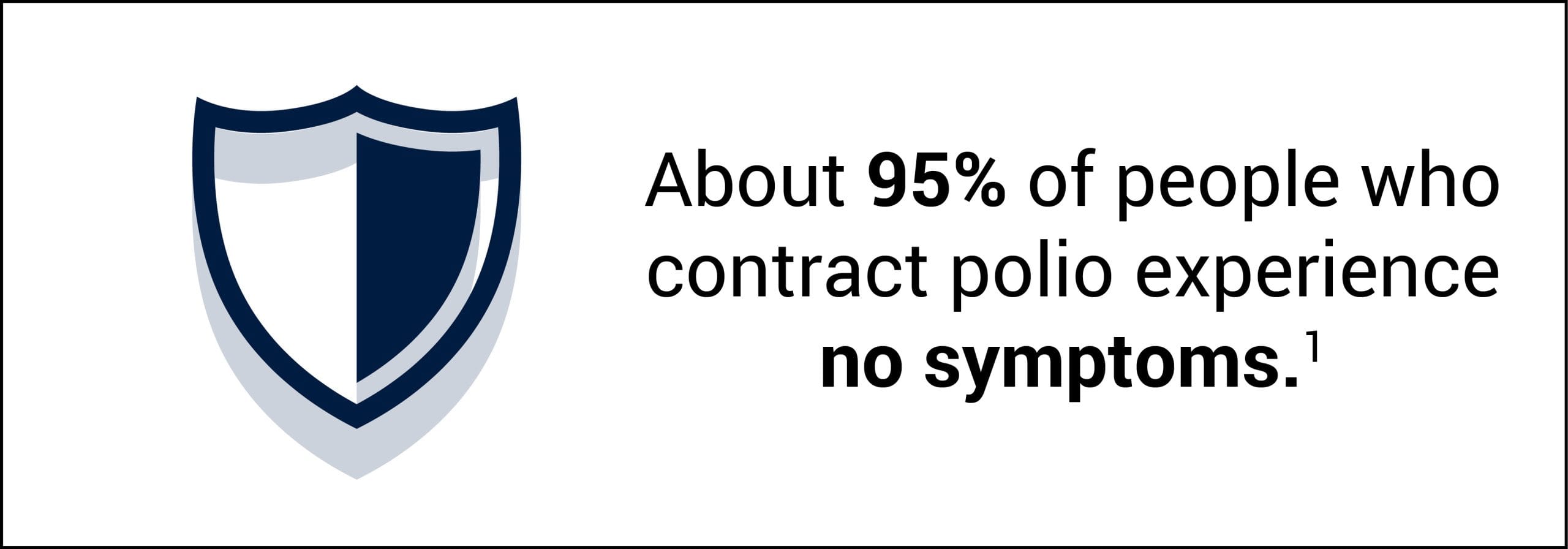

Prior to 1955, before the introduction of the polio vaccine, paralytic poliomyelitis was a disease of low incidence.6 Cases of paralytic poliomyelitis occurred in about 1 in 22,000 (0.005%) in the U.S. population (Fig. 1).7

Figure 1: Before the introduction of the polio vaccine in 1955, paralytic poliomyelitis was a disease of low incidence.

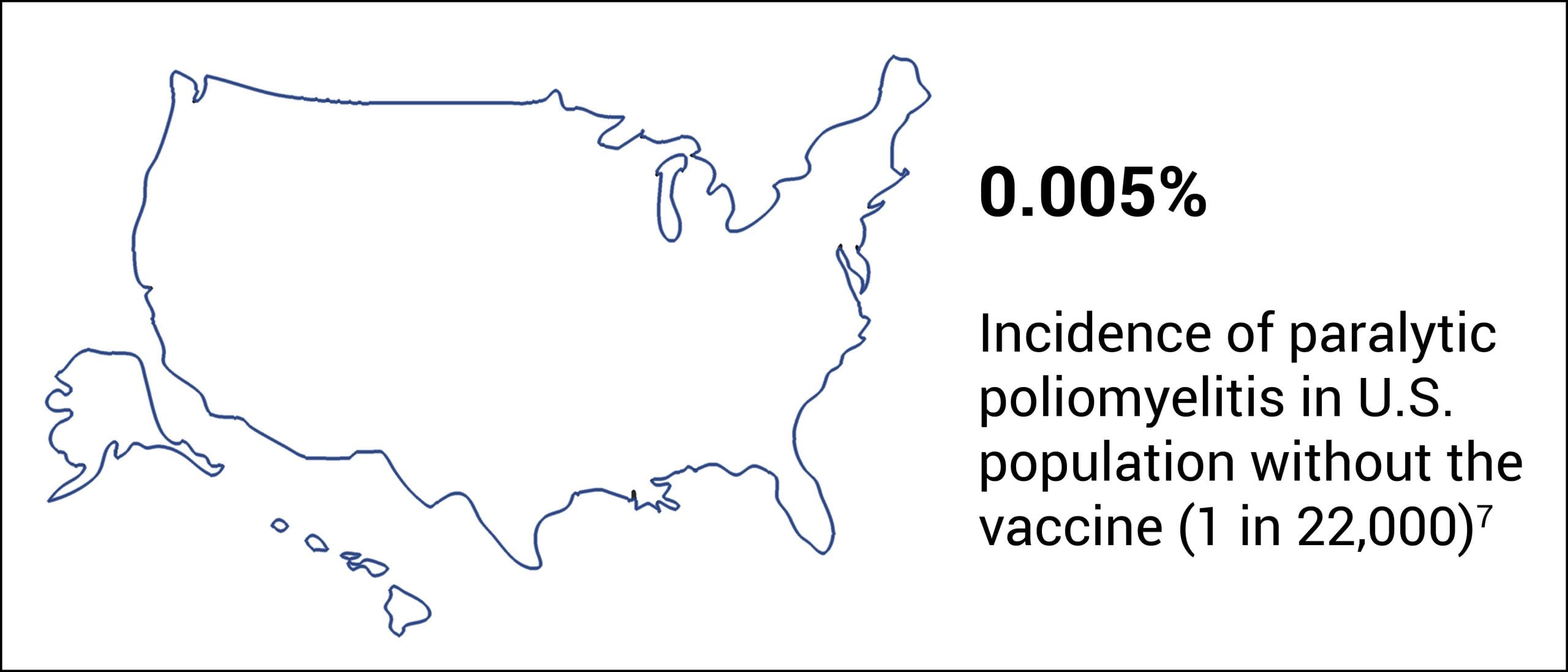

The great majority of polio infections that are fatal or result in permanent paralysis occur in people who have had their tonsils surgically removed (tonsillectomy) or do not rest after feeling sick.

- 71.4% of bulbar (brainstem) paralytic poliomyelitis cases have no tonsils.8

- 72.6% of severe spinal paralytic poliomyelitis cases do not rest after feeling sick.9

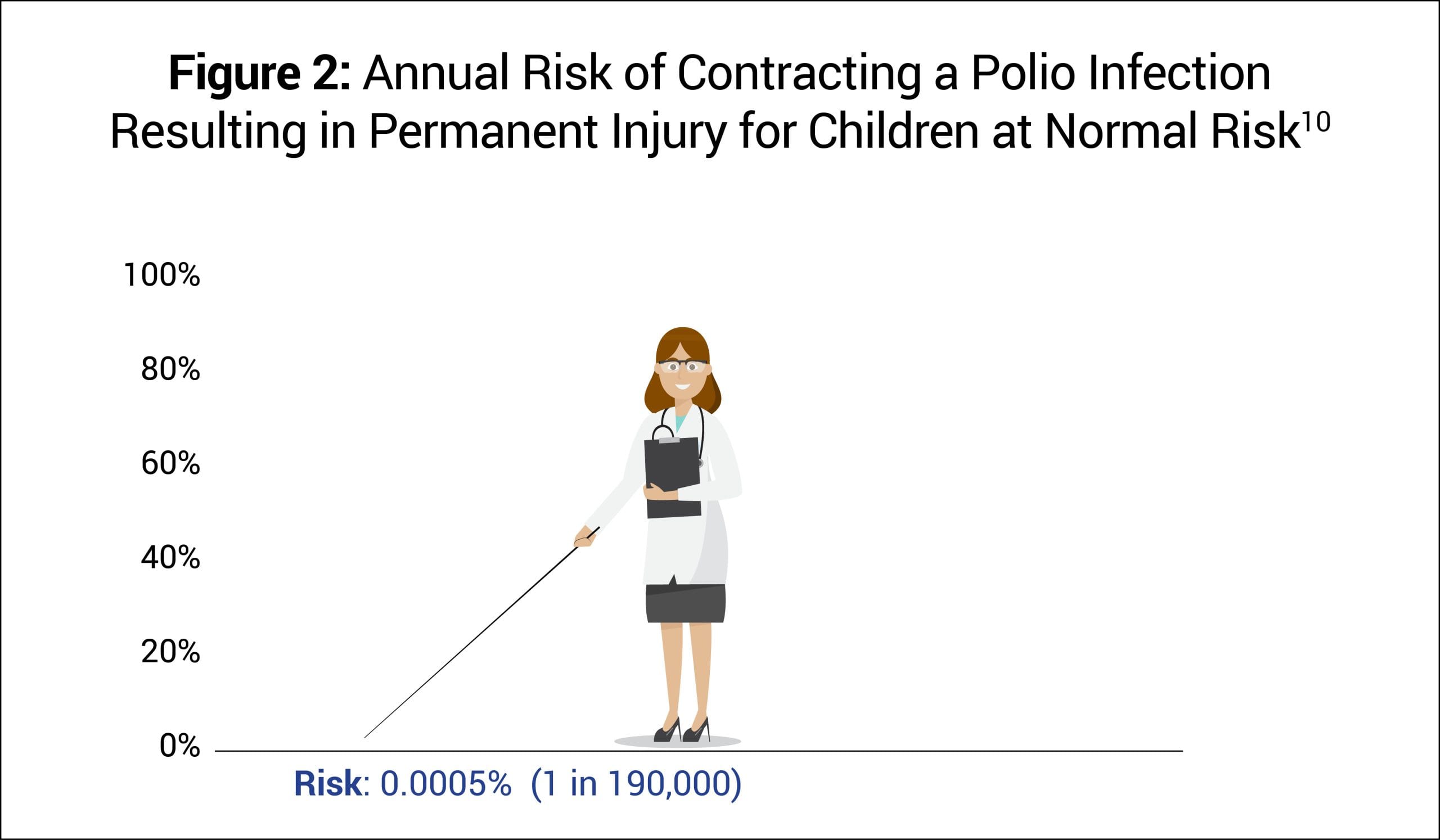

Before the introduction of the polio vaccine, annually about 1 in 190,000 or 0.0005% of children at normal risk (i.e., had tonsils and rested after feeling sick) contracted polio that was fatal or led to permanent paralysis (Fig. 2).10

4. WHAT TREATMENTS ARE AVAILABLE?

Because polio resolves on its own in most cases, usually only supportive treatment is necessary. The most important treatment is rest after feeling sick, as not doing so significantly elevates the risk of infection leading to paralysis.

5. WHAT ABOUT THE POLIO VACCINE?

5. WHAT ABOUT THE POLIO VACCINE?

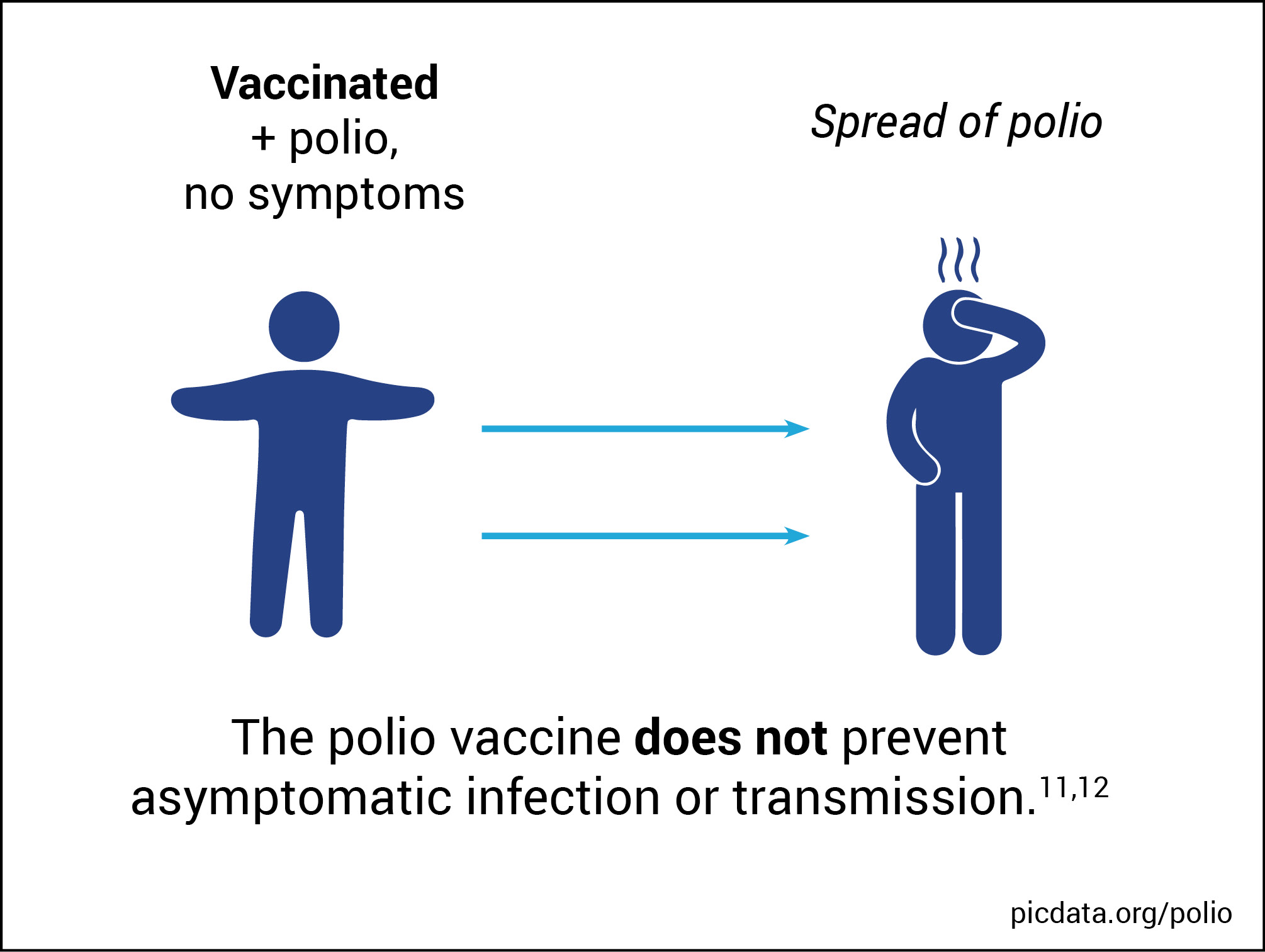

The polio vaccine was first introduced in the U.S. in 1955. It has significantly reduced the incidence of reported (i.e., noticeable) cases of polio infections; however, the vaccine does not prevent asymptomatic infection or transmission.11,12

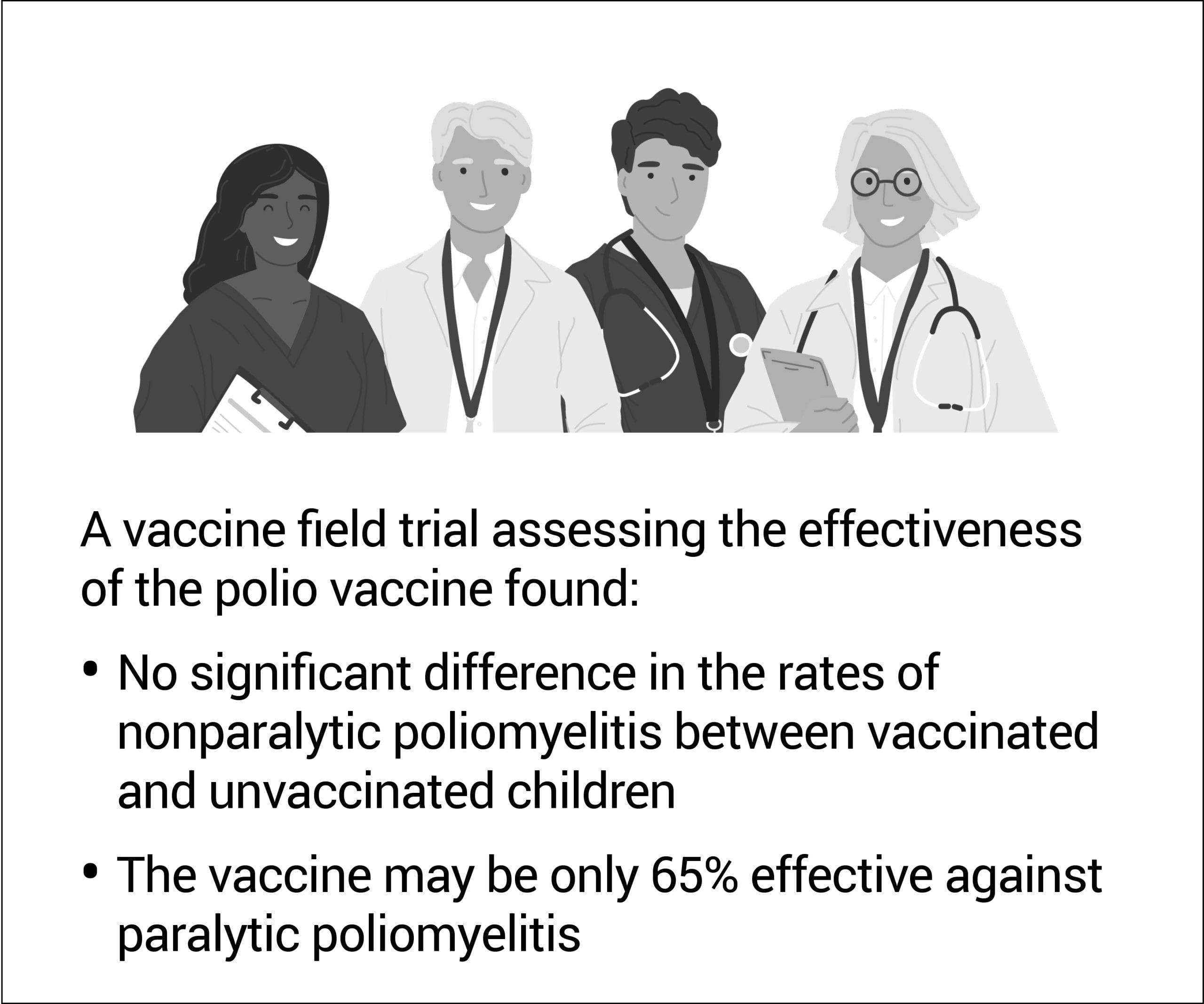

In 1954, a vaccine field trial comparing about 200,000 vaccinated children with about 200,000 children receiving a placebo found that “no significant difference was detected in the rates of nonparalytic poliomyelitis in test and control groups.” Although the trial estimated that the vaccine might be 82% effective against paralytic poliomyelitis, the number of cases observed in the control group was so small that the vaccine may have been only 65% effective: “The estimate would be more secure had [a] larger number of cases been available.”13

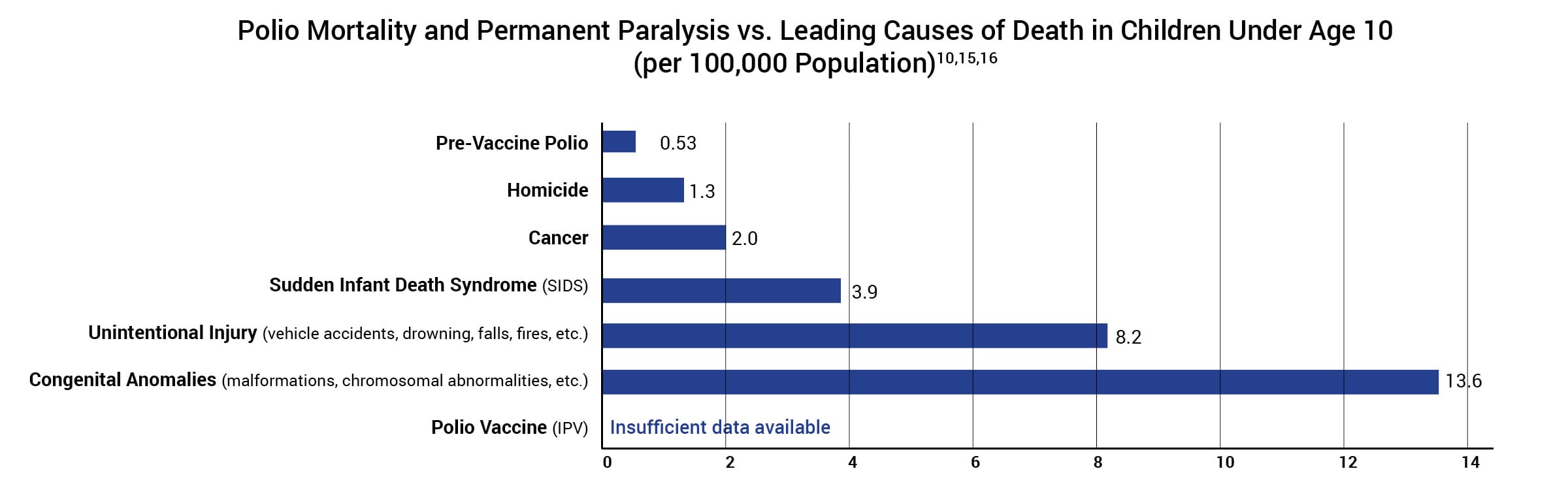

The manufacturer’s package insert contains information about vaccine ingredients, adverse reactions, and vaccine evaluations. For example, “Long-term studies in animals to evaluate carcinogenic potential or impairment of fertility have not been conducted.”14 Furthermore, the risk of permanent injury or death from the polio vaccine has not been proven to be less than that of polio for children at normal risk (Fig. 3).15

Figure 3: This graph shows the polio death and permanent paralysis rate of children under age 10 at normal risk (i.e., have tonsils and rest after feeling sick) before the vaccine was introduced and compares it to the leading causes of death in children under age 10 today. Hence, in the pre-vaccine era, the polio death and permanent paralysis rate per 100,000 was 0.53 for children under age 10 at normal risk. In 2015, the death rate per 100,000 for homicide was 1.3, followed by cancer (2.0), SIDS (3.9), unintentional injury (8.2), and congenital anomalies (13.6). The rate of death or permanent injury from the polio vaccine is unknown because the research studies available are not able to measure it with sufficient accuracy.

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. 11th ed. Atkinson W, Wolfe S, Hamborsky J, McIntyre L, editors. Washington, D.C.: Public Health Foundation; 2009. 232. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/cdc-pink-book-11th-edition-poliomyelitis-2009-p-232.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. 14th ed. Hall E, Wodi AP, Hamborsky J, Morelli V, Schillie S, editors. Washington, D.C.: Public Health Foundation; 2021. 276. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/cdc-pink-book-14th-edition-2021/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. About polio in the United States; [cited 2024 Jul 11]. https://www.cdc.gov/polio/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/polio/what-is-polio/index.htm.

- Magno H, Golomb B. Measuring the benefits of mass vaccination programs in the United States. Vaccines. 2020 Sep 29;8(4)Suppl:9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33003480/; during 1951–1954, there were 7,260 annual cases of paralytic poliomyelitis of which 1,136 resulted in death or permanent disability. Therefore, 84.4% of paralytic cases ([7,260–1,136] / 7,260) fully recovered.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. 13th ed. Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe S, editors. Washington, D.C.: Public Health Foundation; 2015. 300. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/cdc-pink-book-13th-edition-2015/.

- Langmuir AD, Henderson DA, Serfling RE, Sherman IL. The importance of measles as a health problem. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1962 Feb;52(2)Suppl:1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14462171/.

- Magno H, Golomb B. Measuring the benefits of mass vaccination programs in the United States. Vaccines. 2020 Sep 29;8(4)Suppl:9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33003480/; during 1951–1954, there were 7,260 annual cases of paralytic poliomyelitis out of a population of 160 million (1 in 22,000).

- Anderson GW, Rondeau JL. Absence of tonsils as a factor in the development of bulbar poliomyelitis. J Am Med Assoc. 1954 Jul 24;155(13):1123-30. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/295585.

- Horstmann DM. Acute poliomyelitis: relation of physical activity at the time of onset to the course of the disease. J Am Med Assoc. 1950 Jan 28;142(4):236-41. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/287977.

- Magno H, Golomb B. Measuring the benefits of mass vaccination programs in the United States. Vaccines. 2020 Sep 29;8(4):561. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33003480/.

- Cuba IPV Study Collaborative Group. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of inactivated poliovirus vaccine in Cuba. N Engl J Med. 2007 Apr 12;356(15):1536-44. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa054960?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub=pubmed.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. U.S. National Authority for Containment of Poliovirus: interim guidance for potentially infectious materials; [cited 2024 Nov 2]. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/138966.

- Francis T, Korns RF. Evaluation of 1954 field trial of poliomyelitis vaccine: synopsis of summary report. Am J Med Sci. 1955 Jun;229(6):606, 608, 609. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14376387/.

- Sanofi Pasteur SA. Marcy L’Etoile, France: Sanofi Pasteur SA. IPOL (Poliovirus Vaccine Inactivated); 2022 May [cited 2023 May 6]. https://www.fda.gov/media/75695/download.

- Physicians for Informed Consent. Newport Beach (CA): Physicians for Informed Consent. Polio — vaccine risk statement (VRS). IPV vaccine: is it safer than polio? 2023 Aug. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/polio-vrs.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 10 leading causes of death by age group, United States—2015. https://physiciansforinformedconsent.org/cdc-leading-causes-of-death-age-group-2015/.

Published 2023 Aug; updated 2024 Dec